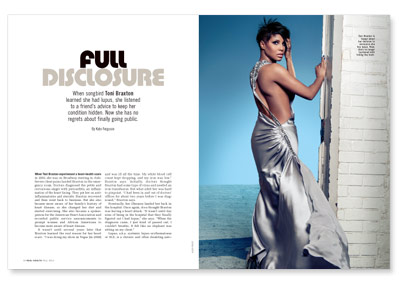

When Toni Braxton experienced a heart-health scare in 2003, she was on Broadway starring in Aida. Severe chest pains landed Braxton in the emergency room. Doctors diagnosed the petite and curvaceous singer with pericarditis, an inflammation of the heart lining. They put her on anti-inflammatories and steroids. Braxton recovered and then went back to business. But she also became more aware of her family’s history of heart disease, so she changed her diet and started exercising. She also became a spokesperson for the American Heart Association and recorded public service announcements to prompt women and African Americans to become more aware of heart disease.

It wasn’t until several years later that Braxton learned the real reason for her heart scare. “I was doing my show in Vegas [in 2008] and was ill all the time. My white blood cell count kept dropping, and my iron was low,” Braxton says. Initially, doctors thought Braxton had some type of virus and needed an iron transfusion. But what ailed her was hard to pinpoint. “I had been in and out of doctors’ offices for about two years before I was diagnosed,” Braxton says.

Eventually, her illnesses landed her back in the hospital. Once again, docs thought Braxton was having a heart attack. “It wasn’t until day nine of being in the hospital that they finally figured out I had lupus,” she says. “When the diagnosis came, I just kind of passed out; I couldn’t breathe. It felt like an elephant was sitting on my chest.”

Lupus, a.k.a. systemic lupus erythematosus or SLE, is a chronic and often disabling autoimmune disease. (The kind Braxton has is discoid lupus.) These types of illnesses occur when someone’s immune system produces antibodies that circulate in the blood and mysteriously attack that person’s normal, healthy body tissues. (Lupus, like autoimmune diseases in general, occurs more frequently in women than in men.)

Another characteristic of lupus is that it is devilishly hard to diagnose. Symptoms of the condition are vague—general fatigue, joint pain and skin rash—and these may come and go over weekly or monthly periods of time. Half of lupus patients experience problems with their organs, such as the heart, lungs, kidneys, liver, brain or bone marrow, explains Daniel Wallace, MD, a clinical professor of medicine at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and the University of California at Los Angeles. “Those patients are usually readily diagnosed within three months. But those who have tired and achy symptoms can take up to several years [to be diagnosed],” he says.

If lupus goes undiagnosed, it can progress and threaten vital organs. “This means early diagnosis is very important,” stresses Wallace, who is also the founder of Lupus LA, an organization that serves the needs of people with lupus and their families across Southern California and that raises awareness and supports lupus research on a national level.

But since there is no single laboratory test to determine if someone has lupus, doctors must do an evaluative blood test, called an ANA, that screens for the condition. “In addition to that, doctors look for protein in the urine, low white blood cell counts, anemia and abnormal chest X-rays that show fluid in and around the lung and around the heart,” Wallace explains. “Doctors may even want to remove a sample of tissue or cells of a rash or mouth sores so a pathologist can examine it under a microscope [a process called a biopsy].”

Wallace recommends people be evaluated for lupus if they are tired and achy and have low-grade fevers, swollen glands and rashes but no obvious infection.

For Braxton, the first red flag that whipped hardest was the pericarditis episode. But it wasn’t until later that she made the connection between that incident and her lupus. When she was finally diagnosed with the condition, Braxton says, she was in full flare. (A lupus flare is when symptoms appear, such as persistent fatigue or weakness, all-over achiness, fever, appetite loss, unwanted weight loss, recurring nose bleeds and unexplained skin rashes, among a slew of other unpleasant signs.)

“When you have lupus, you may have these signs all the time,” Braxton says. “It’s just that you have them more frequently when you’re about to go into a flare.”

Braxton recalls her feelings after the diagnosis. “It wasn’t a triumphant moment when I first found out,” she says. “It was immediate fear. It was surreal at first. I also remember feeling sorry for myself. I immediately thought about my kids and wondered if I would be around for my children.”

Eventually, Braxton came to terms with her diagnosis. She even made her illness the focus of an episode of her reality show, Braxton Family Values, when she disclosed she had lupus to her family.

But before her public announcement, Braxton kept her condition a secret. “A friend of mine who has lupus told me, ‘You can’t tell anyone. You’ll never get insurance; you’ll never get this; you’ll never get that.’ So I kept my illness hidden, like it was a bad thing, like me telling people would do something to them instead of thinking that disclosing my condition would empower me.”

Today, Braxton regrets listening to her friend’s advice. “It made me feel ashamed,” she says. “I initially told people I had heart disease. Everyone was comfortable with heart disease, but they didn’t know why I had it; they didn’t know it was predicated because of my lupus.”

If you’re wondering about Braxton’s health when she glided across the stage on Dancing With the Stars in 2008, here’s the deal. Those shows took place just after she’d been diagnosed with lupus. (Braxton says her doctors were on the set every night the show taped live.)

All but one of her doctors advised her against doing the program because of the strenuous choreography the show demands. The doctor who told her to do the program did so, she says, because Braxton was becoming afraid to enjoy her life. “He said, ‘You’re way too young to do that.’”

Braxton’s daring doc told her other physicians that if she did the show, only one or two things might happen: She’d pass out from chronic fatigue or get booted off the show. “So I got booted off the show; it all worked out,” Braxton says. “I kind of think the producers knew [about my condition]; maybe the doctors or someone said something. I felt sad that I was booted off the show, because this is a competition, but I also felt relieved at the same time.”

Looking back at that time, Braxton recalls being unable to practice the dance sequences as long as necessary. “It takes me a long time to get choreography because I’m not a dancer like Janet Jackson or Britney [Spears], but I’ve got a little rhythm,” she says. “I do remember that it was really challenging for me to remember the choreography because my brain was foggy all the time because of the medications I was on.”

After a pause, Braxton admits that she probably shouldn’t have danced because physically it was way too much for her at the time. Then, in the next moment she changes her mind. “Right now, I’m glad I did it because it helped me emotionally.”

Then that’s quickly followed by a comment from the performer in her, “I would be better on Dancing With the Stars now than I was then—mentally and physically.”

Currently, Braxton works hard to manage her lupus with a combination of drug treatment and lifestyle modifications. “Here I am four years later, and I’m much better,” she says. She notes that she has learned how to properly manage the fatigue that’s part of being an entertainer. Today, Braxton pays careful attention to how many shows she can do over a certain time period, and she dresses properly for the weather. “My flares are fewer,” she says. “Summer is challenging, because with lupus the sun is not my friend, so I make sure I use sunscreen and things like that.”

To address the stress that’s also built into her hectic lifestyle, Braxton finds something to make her laugh, such as an Ellen DeGeneres comedy bit on TV. Beyond that, Braxton says, she tries hard to eat healthy, although she confesses she falls prey to the occasional BLT attack—she has to have “the swine” once in a while even though bacon is a no-no. “But I make sure I eat a cucumber salad a couple times each week,” she says. “Cucumbers keep inflammation down and cool your body off. And I drink aloe vera juice—not every day like I’m supposed to—I try to get it in at least twice each week.”

When she doesn’t eat well, Braxton says, she pays for it. “I get a little puffy and swollen,” she reveals. “When I eat better, my body and mind both feel better too.”

Braxton’s other lupus treatments include common over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as aspirin, Advil or Aleve for mild aches; prescription meds such as the anti-malaria drug Plaquenil for mild, non-organ-threatening disease; high-dose steroids for organ-threatening disease; drugs that suppress the immune system; and targeted therapies. She’s also considering trying Benlysta, the newest drug to be approved for lupus treatment.

“Benlysta potentially has some side effects, but it’s generally very well tolerated and its safety profile is actually better than any of the other drugs we use for lupus,” Wallace explains. “But it’s expensive, so we tend to use it for patients who have active disease despite being treated by steroids or immune suppressants.”

Braxton says she plans to try Benlysta after doing blood work to see if she’s a good candidate for the drug. “I don’t have endorsement deals for any of these products,” she stresses. “I’m just saying, I heard Benlysta helps significantly with lupus.”

Now that her lupus is mainstream news, Braxton feels relieved to speak openly about her condition. Earlier this year, she joined Lupus LA’s executive council to help the organization raise awareness about the condition.

“I wouldn’t want anyone else to live a lie and try to suppress something that you feel,” she says. “That stops you from figuring out how to make yourself healthy.”

Lupus and Heart Disease

Here’s an explanation about how the two connect.

Heart disease is a major complication of lupus and is also a leading cause of death among people living with this autoimmune disease. But, like singer Toni Braxton, many people don’t discover they have lupus until it affects a major organ. In Braxton’s case, that organ was her heart. She developed pericarditis—inflammation of the sac around the heart—which is a common condition among those with lupus who develop heart problems.

Lupus can also cause inflammation of the heart’s muscle layer (a condition called myocarditis) and the lining inside the heart (endocarditis). It can also lead to a narrowing of the coronary arteries that take blood to the heart (coronary artery disease, or simply, heart disease).

In general, people with lupus are at increased risk of cardiovascular disease, which involves hardening of the arteries (atherosclerosis) and can lead to heart attacks or strokes later in life.

What’s more, researchers suggest that lupus be considered equal to coronary heart disease as a known risk factor for heart attacks and strokes.

One study found that women with lupus were more likely than their non-lupus peers to have traditional heart disease risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes. In addition, women with lupus reported earlier menopause onset and showed higher levels of the blood fats triglycerides and low-density lipoprotein (LDL, or “bad cholesterol”).

What lupus does is cause inflammation that aggravates all these factors. This results in an increased risk of heart disease and an accelerated buildup of the plaque that causes atherosclerosis.

To help lupus sufferers avoid these heart problems, researchers suggest they follow a common-sense approach to treatment: Lose weight, stop smoking, lower blood pressure and get a moderate amount of aerobic exercise.

3 Comments

3 Comments