Evusheld—one of the key tools for preventing COVID-19 illness in people who can’t receive or do not respond well to vaccines—is no longer effective against the predominant coronavirus omicron variants, leading the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to withdraw its emergency authorization.

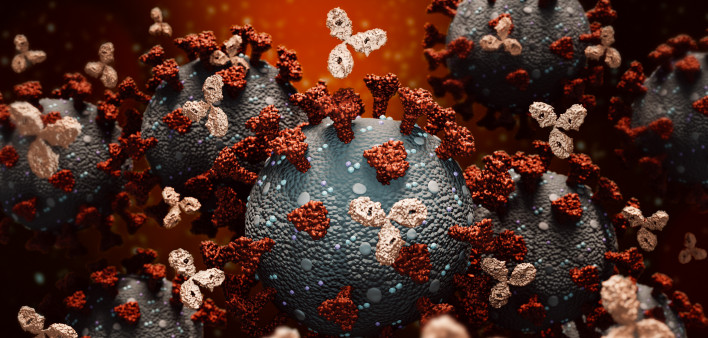

Evusheld, from AstraZeneca, combines two manufactured monoclonal antibodies, tixagevimab and cilgavimab, that target different parts of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and prevent it from attaching to cells. But as the virus has evolved, it has gotten better at evading antibodies, including those that result from natural immunity after infection, those produced by vaccination and those given by injection or infusion.

Some people who are fully vaccinated against COVID nonetheless remain prone to serious illness. In particular, people with compromised immunity may not produce adequate antibodies against the coronavirus. This is the case for some organ transplant recipients who take immunosuppressive drugs; people with blood cancers, such as leukemia or lymphoma; people receiving cancer treatments that temporarily wipe out the immune system (like stem cell transplants or CAR-T therapy) or impair the activity of antibody-producing B cells; and people with advanced or untreated HIV.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and other experts recommend that immunocompromised people should receive a three-dose primary vaccine series plus one or two boosters, for a total of up to five shots. In October 2022, the FDA authorized bivalent boosters from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna that contain components from both the original SARS-CoV-2 virus and the BA.4 and BA.5 omicron variants that began spreading in the United States in the spring of 2022. (Click here for the latest CDC vaccine recommendations.)

For people who do not produce enough antibodies of their own even after multiple vaccine doses, engineered antibodies are a potential lifeline. In December 2021, the FDA authorized Evusheld as pre-exposure prophylaxis (better known in the HIV world as PrEP) administered every six months to prevent COVID in moderately to severely immunocompromised people and those who are unable to receive vaccines due to severe adverse reactions.

In February 2022, soon after the BA.1 and BA.2 omicron variants emerged, the FDA revised its Evusheld authorization to double the dose and cautioned that protection might not last as long as it did in clinical trials. In October 2022, the agency advised that people taking Evusheld may be at increased risk from COVID due to new, more resistant variants; this was followed by a stronger warning in early January.

At that time, the highly evasive XBB.1.5, which Evusheld does not neutralize, accounted for around 28% of circulating variants in the United States. By late January, it made up an estimated 56% of circulating variants. (Click here for the CDC’s variant tracker.)

On January 26, the FDA announced that it was revising the emergency use authorization for Evusheld, limiting its use to periods when the combined proportion of non-susceptible SARS-CoV-2 variants is 90% or less. XBB.1.5 plus other non-susceptible variants currently exceed that threshold, so Evusheld is not currently authorized for use in the United States until further notice. The agency advised providers to keep existing stocks of Evusheld in case the variant mix changes to favor susceptible strains.

What Can Immunocompromised People Do Now?

The withdrawal of Evusheld puts immunocompromised people in a difficult position, relying on non-pharmaceutical interventions such as masks and social distancing—which are increasingly less common among the population at large—and treatment if they do catch COVID. But treatments are currently limited.

No other therapies besides Evusheld have been approved for COVID PrEP, though AstraZeneca is working on a next-generation monoclonal antibody. One by one, as variants emerged, the various monoclonal antibody therapies used for post-exposure prophylaxis or treatment became ineffective and the FDA withdrew its authorization.

Convalescent plasma from people who have recovered from COVID is no longer widely used, but it could potentially be beneficial for treatment.

The oral antiviral medication Paxlovid (nirmatrelvir plus ritonavir) may be an option, but it can interact with many drugs used by people with immune-compromising conditions. And it can be difficult to obtain. Some experts recommend that older people and others at high risk of severe COVID should have a plan to access the treatment—or even get a prescription in advance and keep a course on hand. Lagevrio (molnupiravir) is another, albeit less effective, oral antiviral. Veklury (remdesivir) is now approved for hospitalized adults and children and those who are not hospitalized but at risk for severe illness, but it requires daily IV infusions.

CDC

In the wake of the FDA’s withdrawal of Evusheld, the CDC released new information about COVID prevention and treatment for people who are immunocompromised in the context of currently circulating omicron variants. The CDC notes that vaccination “remains the most effective way to prevent SARS-CoV-2-associated serious illness, hospitalization and death.” Many people with compromised immunity do respond to the vaccines to some degree, especially if they’re up to date with boosters.

“It is important that persons who are moderately to severely immunocompromised, those who might have an inadequate immune response to COVID-19 vaccination, and those with contraindications to receipt of COVID-19 vaccines, exercise caution and recognize the need for additional preventive measures,” the CDC authors wrote. “In addition, persons should have a care plan that includes prompt testing at the onset of COVID-19 symptoms and rapid access to antivirals if SARS-CoV-2 infection is detected.”

Click here for more news about COVID-19 treatment.

Comments

Comments