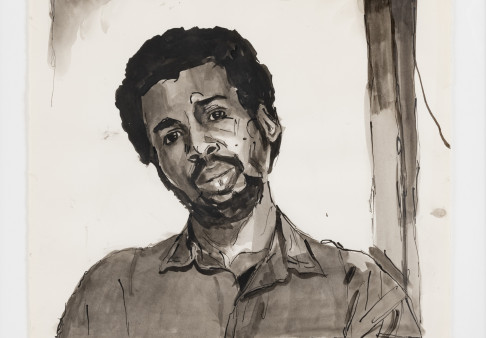

Although Darrel Ellis, a Black artist known for his conceptual portraits of family and friends died of AIDS-related illness in 1992 at age 33, his work and life story—including HIV, racism, queerness and African-American culture—continue to resonate. Ellis’s father, Thomas Ellis, a studio photographer in Harlem and the South Bronx, was shot and killed by police two months before Darrel was born in 1958.

Darrel Ellis died just months before his work was featured in New Photography 8, an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). “Ellis was a prolific artist who briefly worked as a security guard at MoMA in the late ’80s. He was also a black gay man who died of AIDS,” wrote art critic Ariel Goldberg in Art News.

“Ellis’s pictures,” Goldberg continued, “captured a family history that ruptured: [His father] died at the hands of plainclothes police over a traffic dispute a month before Darrel was born. In the early years of appropriation, Ellis translated his father’s black-and-white snapshots into figurative drawings and paintings of a matching grayscale palette, as if to memorialize the parties and family milestones.”

Ellis also transformed the images of other photographers—including Peter Hujar and Allen Frame—to create his own unique works. For a prime example, check out this Cooper Hewitt article to view a 1994 Day Without Art poster by Visual AIDS; it is built around a self-portrait Ellis painted from a photograph by Robert Mapplethorpe.

Ellis’s portraiture is the subject of A Composite Being, a solo exhibition currently at the Candice Madey gallery in New York City (view images from the exhibition in the slideshow above). Another solo show is slated for August in Switzerland, and a major monograph is scheduled to be published this fall by the organization Visual AIDS (visit VisualAIDS.org to view nearly 100 works by Ellis, including his self-portraits based on photos by Mapplethorpe and Peter Hujar).

POZ emailed gallery director Candice Madey to learn more about Ellis’s work and the current show. Our correspondence has been lightly edited.

What drew you to Ellis’s work, and when did you first discover him?

I was introduced to the work by my friend and colleague Allen Frame [who is a photographer and writer]. The combination of material experimentation and sensitivity, beauty and tenderness in the depictions of the people around him was compelling. I got a sense of who Darrel was as a person by the way he depicted his friends and his family, and I was so charmed. I wanted to know him.

The collection of Ellis’s work at your gallery spans about a decade. How do the pieces fit into his larger body of work?

Sadly, Darrel died young, at age 33. Most of his work was made between ages 20 and 32. So this work represents that range and is indicative [of his other work]. I focused on portraits, which were a large part of his work. But he also included cityscapes, domestic interiors and abstractions in his work, and those are not represented here.

How would you describe the common themes and subject matter of his works?

Friends and family, primarily. And secondarily, would be the spaces those people inhabited. There is an interest in intimacy and a relational psychology among the people depicted.

What makes his work relevant today?

Darrel’s father was killed by the police two months before Darrel was born, and Darrel suffered from never knowing him. He died young of AIDS-related causes and, like so many at this time, did not have adequate health care at the end of his life. We have to acknowledge the long history of these systemic injustices and the effects it has had on individuals and the broader society—imagine the masterpieces that would be with us today if Darrel had access to more financial resources when living and had a lifetime to work.

Darrel’s work, however, does not address these issues topically. He presented us with beautiful, personal, intimate moments of a family—something that everyone can understand and relate to. It’s this accessibility and empathy that resonated with me.

Similarly, does any of his work deal with the subject of AIDS or queer identity?

He did not address these ideas literally in the work. However, in his journal, he was thinking deeply about them. He questioned the Eurocentric history of art that was handed down to him and explored how to exert a Black identity that was true to himself.

How did this show come about?

Again, through Allen Frame. He approached me in 2020 about the possibility of representing the estate. I was honored. He is an extraordinary connector of people and advocate for other artists. There is something inspiring about the idea of artists and friends taking care of each other—and, in this case, even 30 years after Darrel’s death.

Tell us about the title of the exhibit—A Composite Being—and what it means.

I pulled the title from an excerpt in Darrel’s journal from 1989:

What is a human being? A composite being.

What is it we see and feel and experience about another human being?

Darrel was interested in Buddhism and other spiritual traditions. He spoke a lot about the interconnected nature of life, and the idea of an introduction to the artist and his work via portraits of the people close to him felt apropos. It also seemed significant in late 2020, when I was thinking about the show while organizing it during COVID and during a time of much isolation. I missed my family and friends. And I thought about Darrel and the way he used his work to understand the people around him, to be closer to them. I thought about presenting the multifaceted complexity of Darrel’s life, history and work and [was] hoping to share that with the viewers.

Finally, is there anything else you’d like the POZ reader to know about Ellis’s work or your gallery?

The show is on view through May 28; however, if you miss it, we have comprehensive photos on the Candice Madey website. I would love for more people to be aware of Darrel’s extraordinary output. A Brooklyn Museum show [The Slipstream: Reflection, Resilience, and Resistance in the Art of Our Time] includes Darrel and opens May 14. And Matte Editions recently published a book [Fever] by Allen Frame of his own photographs, including a number of beautiful photos of Darrel in the studio and with friends.

Comments

Comments