At first, my mother’s memory loss wasn’t alarming. The first time she forgot something major, my siblings and I were just em-barrassed. We thought it happened because she was getting older and more forgetful. My older brother and his wife had invited my mother, my sister and me to dinner and were waiting for us when we pulled up in front of their porch. When we got out of the car and my mother got close to the house, she pointed to my brother’s wife and asked if she was his mother-in-law. The mistake was jarring because his mother-in-law had died one year earlier—a fact my mom was very aware of.

At the time, my sister and I exchanged questioning glances and my brother seemed a little annoyed. His wife didn’t say anything, but she gave a nervous laugh. Then, the fog seemed to lift from my mother’s mind. She sheepishly apologized for her mistake and we went into the house. Nothing more was said about it until about a year later when her memory failed again. One day, I took her to visit the old neighborhood where we’d lived. As we drove along the streets she once loved, she looked around with a blank stare. That’s when I became alarmed.

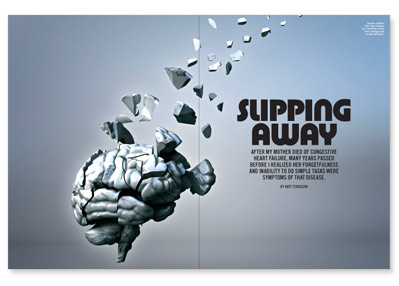

Eventually, months later, doctors diagnosed my mother with congestive heart failure, but no one mentioned that this cardiovasuclar illness might cause memory loss or impair her cognitive skills.

In the first stage of the illness, the most dramatic signs of my mother’s heart condition were all physical. The illness reduced her heart’s ability to pump blood efficiently through her body, and her kidneys responded by causing her to retain fluid (water) and salt. The fluid built up in her lungs and pooled in her legs and ankles, so it became difficult for her to breathe and walk.

But as hard as it was watching her battle these challenges, the thing that saddened us the most was seeing my mother transform from a vibrant and involved woman into a flat-voiced, unresponsive stranger who seemed totally disconnected from her surroundings. Eventually, because she easily lost her balance, I had to get a wheelchair to help her move around the house.

The diagnosis and my mother’s decline echoed the results of a Swedish study that showed heart failure is associated with an increased risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in older adults. Dementia is a broad-based term for a group of disorders that diminish cognitive functioning and cause memory loss, disorientation, impaired judgment, personality changes and the inability to plan. Alzheimer’s is a common form of dementia that develops slowly and gets progressively worse. In addition, the condition can become severe enough that it can make doing everyday tasks difficult.

One major reason why people develop congestive heart failure is that diseases such as hypertension weaken or stiffen the heart muscles. In addition, during the course of these illnesses, the body’s tissues can demand more oxygen, taxing the heart beyond its limits.

When you have high blood pressure, the heart has to squeeze against the higher pressure, so the left side of the heart becomes thicker. When the hypertension progresses, the heart becomes very stiff and it causes the same symptoms as if the heart isn’t squeezing correctly, says George Sokos, MD, a cardiac specialist in heart failure and heart transplant at Canonsburg General Hospital in the West Penn Allegheny Health System in Pennsylvania. “By the time someone gets to see me, it may not be too late, but they’ve already been affected by the disease—so I really try to stress prevention,” Sokos says.

According to Sokos, hypertension is serious enough to be considered first-stage heart failure as redefined by the American Heart Association.“If you have hypertension, and you don?t have any symptoms of heart failure, we consider you [as being such a high risk] that we really want to push for treatment of heart failure,” Sokos says.

According to the most recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention statistics on heart failure, my mother was not alone. Almost 5.8 million people in the United States have heart failure, with about 670,000 people diagnosed with the illness each year. Doctors who suspect that a patient has the disease can attempt to confirm that diagnosis with a variety of blood tests or an electrocardiogram, a test that measures and charts the electrical impulses traveling through the heart, says Michael Farkouh, MD, an associate professor of cardiology at Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

After my mom was diagnosed with heart disease, her cardiologist placed her on a program that restricted her salt intake and the amount of wine she could drink. He also placed her on drug treatment.

For a while, the treatment seemed to stabilize my mother’s condition. But, gradually, the disease began to gain ground, and soon it became clear to us that she was becoming tired of the struggle. The end came swiftly on a summer evening just after my sister and I had prepared my mother for bed. The next day, we were scheduled to have a nursing attendant come to help us, but that was no longer necessary.

Today makes 12 years since my mother’s death. Doctors know so much more now about congestive heart failure and the other illnesses it can trigger. For many years, because my siblings and I didn’t know that my mother’s condition might cause dementia, we wondered if getting older would automatically put us at risk of the cognitive decline she experienced. Like many people, we believed that the dementia my mom developed was a function of aging.

But according to the Alzheimer’s Association, cardiovascular diseases can damage blood vessels anywhere in the body, including those in the brain. Such damage can rob the brain cells of vital food and oxygen. What?s more, blood vessel changes in the brain are linked to vascular dementia, and this may cause a patient to experience faster cognitive decline or more severe problems.

This is why a treatment strategy to protect the brain is also heart smart. These strategies recommend that people don’t smoke; they take steps to keep their blood pressure, cholesterol and blood sugar within suggested limits; and they maintain a healthy weight.

In addition, doctors also prescribe drugs called cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine to treat symptoms of illnesses that affect memory, thinking, language, judgment and other thought processes.

What’s key is that doctors are able to diagnose cardiovascular disease early; with treatment, there’s usually a better chance they’ll be able to control a patient’s heart disease. Aggravating or failing to control cardiovascular conditions, such as congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, may harm the cognitive function of patients with dementia, according to the American Medical Association. That’s why the group recommends paying attention to, and aggressively treating, both cardiovascular disorder and dementia when they coexist.

Years ago, when my mother was diagnosed, the cardiologist only treated her heart disease. By the time he did prescribe a drug called Aricept (a cholinesterase inhibitor) to treat my mother’s dementia, her congestive heart failure was too advanced for the med to help much. She fought until her weakened heart surrendered, and then she succumbed to the disease.

Today, many patients with the same condition lead active, satisfying lives because of more effective drug treatments for heart disease and the dementia that sometimes accompanies it. What’s crucial, says Farkouh, is that the disease is found and treated in its earliest stages.

1 Comment

1 Comment