|

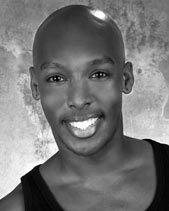

After Terry Dyer graduated from college in 2005, one year later he discovered he was HIV positive. At the time, Dyer worked as a recruiter in the staffing and employment industry. The Stop AIDS Project was one of his clients. Then Dyer had a chance conversation with the organization’s executive director. During the chat, Dyer discussed what being a gay black man meant to him and the importance of being able to live a healthy lifestyle. Soon after, the executive director offered him a job. Dyer became the program manager of the Stop AIDS Project’s Our Love Program in San Francisco. For him, the job was more than just a challenging opportunity. The position also offered him a very personal way to reconnect with the black gay community. It was something that he says had been missing in his life for a very long time. Plus it also provided him with a way to do the kind of philanthropic work that satisfied him most: helping people and giving back to his community.

As the name suggests, the Stop AIDS Project, established in 1985, works to prevent HIV transmission among all gay and bisexual men in San Francisco through multicultural, community-based organizing. The goals of the Our Love Program are two-fold. The first is to bring education, outreach, advocacy and awareness about HIV/AIDS prevention to the community. The second is to address the increasing isolation of the black, gay community. The program will accomplish this, Dyer says, by increasing their visibility in the Castro and building a community of support for them.

Dyer spoke with POZ about the challenges and rewards of doing HIV outreach among African-American men in the Castro.

In the videos on the Stop AIDS Project’s website, a lot of people talk about bringing diversity back to the Castro. What is that all about? Why is it so important?

The Castro is really the gay mecca of the world. When people think of moving to places where they feel comfortable and where others are accepting of their sexuality, I think people tend to flock here to the Castro. About 30 to 40 years ago, there was a large presence of African-American gay men here who felt accepted and like they belonged in this community and were a part of it. Over the past 10 to 15 years that has changed drastically.

What happened to change it?

Property values and taxes started to increase. The economics drove people out of the Castro. In addition to that, five to seven years ago, I believe, there was a big scandal. A bar owner in the Castro started carding and, some people felt, specifically targeting black people when they came to his bar. In addition, the same bar owner bought out and took over the only black club in the district. With that establishment gone, [gay black] people stopped coming into the Castro as well.

Is the area now regaining its original flavor as a diverse gay mecca?

We’re trying to. It’s definitely a work in progress. We’ve been developing more allies, people who believe in what we’re trying to achieve, but there still are a few bumps in the road that we have to negotiate. We go out to different bars to help build community. Our goal is to confirm our presence in the area so we can build acceptance. We also do more work outside the bars, too, that focuses on building community. These efforts are inclusive. People from all walks of life are invited to all of our events. We only have one event in particular that is for black gay men only.

And which one is that?

It’s a discussion group that I hold twice a month and it’s called JAMII [a Swahili word that means family]. In that discussion group, we talk about anything and everything under the sun—relationships, interracial dating, dating in our own community and leadership building and skills. We talk about things that really and truly affect people’s lives. That’s the one event we hold so people can feel really safe and comfortable and say whatever they want to say.

What parts of the Our Love Program specifically address HIV/AIDS concerns?

The first is education, outreach, advocacy and awareness of HIV/AIDS prevention. That also includes increasing testing among the black gay community. At our bar nights, we have an RV [recreational vehicle] stationed outside neighborhood bars where we do testing. The reason we do testing at bar nights is because when people drink alcohol, it loosens their inhibitions and it affects their ability to make good decisions, which is directly linked to transmission of the virus. We also do testing at our calendar release parties. [We produced a black men of the Castro calendar.] The second is decreasing the isolation and stigmatization of the black HIV/AIDS community. We’re doing that by increasing our visibility in the Castro and promoting our presence to build a community of support.

What has been the response to these initiatives?

I’d say that 80 percent of the people who have been to either our community events or other programs have been fully supportive. I have to admit that when I signed on to this position, I didn’t realize the magnitude of it. I receive e-mails, phone calls and text messages from people throughout the community saying, “Thank you so much for what you are doing,” and “This really is changing the face of our neighborhood and our community.” I get messages from people who aren’t African American stating, “What you are doing is wonderful.” We have different Facebook pages and blogs and Twitters. People post comments that support and thank us for the work we are doing. They tell us it’s needed and it’s nice to see that the diversity is starting to come back to an area that is supposed to be so accepting and comfortable for diverse groups of people. But with the good, we’ve also got to take the bad. We do receive negative comments as well. Black gay people have told us, “If you don’t feel accepted [in the Castro], go somewhere else—go across the bridge to Oakland or move to Atlanta where there is more of a black presence or a black gay community.”

You say that this is from within the black gay community in particular? I don’t understand that.

We receive negative comments from time to time from various members of the black gay community, and those are typically the folks who choose not to come and hang out in the Castro or have decided to move away from the Castro for various reasons. But, to be honest, we welcome negative feedback because that allows us to use it as an educational opportunity, to let them know what our motives are. And what’s driving us is to let people know the common denominator here is we are all gay and we should all be able to work and play together.

Do you feel that part of this negative feedback is a class thing?

Some people have said that it does revolve around class and the socioeconomic status of certain people in the community. Some of the feedback we’ve received about some of our videos is that the people in them seem very “uppity” and “white-washed.” But it’s not about that. Those people are educated, and they are articulate, and they want to make sure that they are being represented well. There are many different population groups represented in the community of the Castro.

What are some of the main challenges that you face in trying to promote positive images of black gay men in the Castro?

When we want to put up posters and fliers to advertise different events, some folks will not let us post them in their stores and window fronts. Then, when we have volunteers put up posters in the neighborhood, people tear them down or slice through them and deface them. Now I think of it as something that goes along with the job. It took me a little time to realize that when I started. How I respond is to just put more posters up, so that’s OK. But there are small victories. I was very happy when five stores in the Castro began selling the calendars. That was definitely a step in right direction.

In your opinion what difference has the Stop AIDS Project made in the fight against stigma and prejudice?

That’s where our community events come in. When I first joined the organization in 2009, one of the first things I wanted to do was one big community party. I felt we needed to brand the program more, get it out there and introduce it to the community. The program just celebrated its 10-year anniversary, but no one really knew it was here. I’ve been living in San Francisco for four years, but I didn’t know it existed. In July 2009, we held a huge event in one of the big parks in the Castro. We had a big, free barbecue for everyone in the community. We fed them, and then we watched the movie The Wiz and had a sing-along. To be honest, that event set the tone for everything else we’ve done. I’ve had people tell me we made history by bringing all these people together. I’d bet there were 200 to 300 people at that event. And it was not only African Americans and gay people; all ethnicities and people of various sexual orientations were represented that night, including heterosexual families in the neighborhood, elderly folks and young people. It ran the gamut of people present in the community.

What upcoming HIV/AIDS events would you like us to know about?

At the moment I’m working on one of our biggest events: a two-day workshop in February. It’s specifically for black gay men, especially those who are newly positive. In the workshop we discuss everything being HIV positive entails. We’re planning to have speakers come in and present on different topics, such as benefits, medications and health care. We are trying to get African-American doctors, so the people who are there will really feel like this is specifically for them. We want them to feel this is a place where they’ll feel comfortable sharing their experiences, talking about their feelings and emotions and how to deal and cope with these things. We’ll have small groups so that we can talk about getting people to identify what it means to live with the virus.

What specifically will this workshop and others like it do to link people to care?

We also work with the AIDS Health Project. What that entails is immediate testing for people who want to get tested right away. Then we send them directly to the AIDS Health Project, which is just a few blocks from us. We partner with a lot of different organizations in town that offer more health care, more medical attention people may need. We also work very closely with the Black Coalition on AIDS (BCA) as well as the Black Brothers Esteem (BBE). What they do is work more closely with clients. They have case managers and provide more health services as well.

What is the importance of community support to HIV/AIDS advocacy?

First and foremost, I think it brings a very positive and healthy face to HIV and AIDS. There is still such a negative connotation surrounding HIV/AIDS, but there doesn’t have to be. It’s not the end of life when someone tests positive. You still can live a long, healthy life. Unfortunately, because of a lack of education or resources or being unaware, people don’t know that. People still think that we are stuck in the mid ’80s, early ’90s when the medications and technology weren’t where they are today. The second thing is that community support offers a chance for people to celebrate the diversity of having different people in their neighborhoods. That’s what we’re trying to do in the Castro. Although there is plenty of diversity, we all have a common goal: to be healthy as we work, live and play together.

For more information about The Stop AIDS Project, its programs and upcoming events, click here.

3 Comments

3 Comments