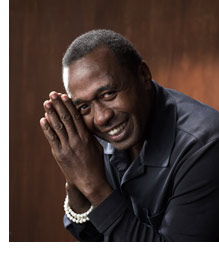

Between 6 and 8 million people in the United States have some form of language impairment, according to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communnications Disorders. Entertainer Ben Vereen became one of those millions with a speech problem in 1992 when he suffered severe injuries after being hit by a truck. Those injuries forced doctors to perform a tracheotomy on Vereen. This surgical procedure is one physicians use on the neck to open a direct airway through an incision in the windpipe. After he recovered from the surgery, Vereen had to work with speech-language pathologists to learn how to speak again. He says the experience taught him that we must always work to overcome the challenges life sends our way.

How did the automobile accident affect your speech exactly?

|

I’m a singer and a speaker and so it was very devastating to me to wake up in the hospital and not be able to talk. When I first tried to speak, I had these tubes in my vocal chords and couldn’t make any sound. The vehicle had struck me in the midsection and, I guess because of all that was going on there, the doctors decided I needed a tracheotomy in order to save my life. I’m thankful for that.

What concerned you the most about what effect this accident might have on your entertainment career?

Well, it wasn’t only about my career but also my life. When you’re born with the ability to speak, you’re not versed in being able to communicate like those people who don’t have speech ability; they speak wonderfully with their hands and gestures. I wasn’t educated about that and was unaware [of ways to speak without using my voice]. I had to re-learn how to speak. At times, I thought, oh my god I won’t be able to talk; nobody will understand or how will I communicate? Years ago I had an operation on my vocal chords. At the time, I knew my voice would come back. The doctor who operated on me gave me a pad and told me I had to be able to communicate, so I would write things out. The interesting thing is that when you can’t talk people have the tendency to believe you can’t hear, so I could imagine what people who can’t talk have to deal with on a daily basis. I got a taste of what that was like. There I was with a tracheotomy not knowing if I would ever get my voice back. I was concerned about what I was going to do with my career, and the doctors said I should think about [doing] something else. That’s when I found out about occupational therapy.

What did your doctors tell you about your condition?

Well, the doctors at UCLA said it would be three years before I talked again. But the great thing was I had a wonderful doctor, who introduced me to another physician who’s the one who really gave me back my voice. Dr. William Riley, and his wonderful wife, Dr. Linda Carroll, worked with me on my speech and vocal exercises and assured me this therapy would help me get my voice back. They said, “You will sing again, but it will be different.” And I am singing again and I am speaking differently. But I’m speaking much better. What’s so wonderful about speech therapy is it introduced me to this whole arena of people who are wonderful in my life.

How long did you work with speech-language pathologists?

I still do on and off. I always go to check up whenever I’m in New York. I see Dr. Carroll; she comes to my shows! She’ll sit in the back and put me through exercises to make sure that my speech is correct. She was at an American Speech-Language-Hearing Association conference in Louisiana with me and came backstage. This is the reason I love her. She escaped from the audience and just came backstage and said, “OK, let’s see how you’re pronouncing, how your voice is working.” She makes me do the exercises; she’s family. And that’s what’s so wonderful about what occupational therapists do. They’re concerned not just about getting you well but about your life because we are all in this communicating arena together, are we not? And because of speech therapy, I am able to speak on various topics. I’m able to go out and spread the word. Right now, I am setting up STAND [a diabetes awareness campaign]. The campaign is [to support] people taking a stand for their diabetes, and so I am able to talk about that with more enthusiasm because of my speech therapists.

How long were your therapy sessions?

The time they allot you in the hospital is, maybe, a half hour or an hour. I would go and work with mu speech therapists for an hour or two and then go back to rehab at Kessler Rehabilitation Center. I would also work on physically strengthening myself. But the voice coming back was real interesting, was real strange.

How would you describe that experience?

Like being on this side of Jordan. It was wonderful because I crossed over. If I had stayed in the middle and I had drowned, this wouldn’t be such a good conversation we’re having right now. But that’s on the patient or the person who’s going through it because the doctors are guides. If you do your work and complete their homework—they would work with me an hour—then I’d go back to the rehabilitation location at night and I would do the exercises they gave me. Doctors can show us the way, but we’ve got to do the work. We’ve got to show up. We can’t just lay there. I love when people say, “God’s gonna heal me,” and then get back in bed. You’ve at least got to take a step toward recovery.

What were some of these exercises you performed?

The exercises consisted of forming words, pronouncing consonants and I practiced vocal scales.

What was the most difficult thing for you during this period and doing this therapy?

The most difficult thing in the beginning was not knowing if I could [do speech therapy]. Also difficult was getting my fear factor out of the way. Fear is a challenge that makes you stronger if you embrace it to find your strength. Fear throws up an obstacle, you know, boom can you do it? And sometimes people look at the fear and panic. They run instead of embracing it and valuing their strength. Fear was my initial response, but my determination was there. I had to do this. I’ve been blessed to have angels around to guide and help me as I go.

People take their voices for granted, how do you feel about having the ability to speak right now?

Actually, I can’t speak for everyone else, but I don’t take my voice and speech for granted any more. And I’d just like to say to other people that they shouldn’t either.

Comments

Comments