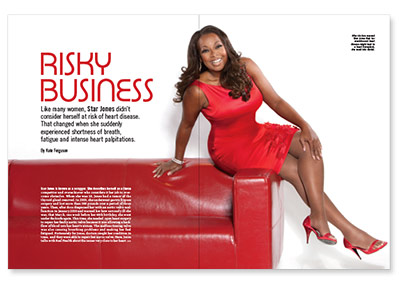

Star Jones is known as a scrapper. She describes herself as a fierce competitor and overachiever who considers it her job to overcome obstacles. When she was 19, Jones had a tumor of the thyroid gland removed. In 2003, she underwent gastric bypass surgery and lost more than 160 pounds over a period of three years. Then, after docs diagnosed her with an aortic valve malfunction in January 2010 and warned her how seriously ill she was, that March, one week before her 48th birthday, she went under the knife again. This time, she needed open heart surgery to repair her faulty aortic valve because it was allowing a backflow of blood into her heart’s atrium. The malfunctioning valve was also causing breathing problems and making her feel fatigued. Fortunately for Jones, doctors caught her condition in time, and they were able to repair her aortic valve. Here, Jones talks with Real Health about the issues very close to her heart.

Before being diagnosed with heart disease, were you concerned about your risk of heart problems?

I’d never really heard people talk about women and heart disease. I really thought it was, like I’ve said many times, an old white men’s disease. It really wasn’t until I took control of my weight that I started to focus on health. Prior to weight loss surgery, I can honestly say to you that in my adult life I had never thrown, run for or kicked a ball, period. I was extremely naive. I like to take full responsibility for my condition because I can take full credit for changing my life. When the doctor said that you needed open heart surgery, how did you react?

When the doctor said that you needed open heart surgery, how did you react?

I asked, “You need to crack my chest again?” At 19, I’d had thoracic surgery to remove a tumor on my thyroid gland; doctors cracked my chest open to get to the tumor. I actually was told that without the surgery, I probably wouldn’t live another six to nine months. Then, I [was told I] needed to go through that process again in my 40s. I really stuck my head in the sand. I said, “I don’t think so.” Then I got on a plane and went to St. Bart’s to join my girlfriends on a yacht. They didn’t have heart disease on the yacht; they had champagne and party and fun. Luckily my girlfriends on the trip had a bit of a “come to Jesus” meeting with me. They talked about how important it was for us to not be afraid when we are confronted with something, and that we could get through this together. It was that conversation, as well as subsequent conversations with my parents, that convinced me. I returned to New York and I talked to one of my dearest friends, Dr. Holly Phillips, a CBS medical correspondent, who is also my internist. When I talked to her, I told her what the doctors had said. I’ll never forget it as long as I live. When I handed my report to her on the way to the cardiologist, she said, “These are your numbers? You’re having this damn surgery.”

Was there anything special, apart from mentally, that you did to prepare for the surgery?

Well, I am severely anemic, but I’d learned to manage it. The last thing anybody wanted was for me to need a blood transfusion on the table. The doctors wanted to get my blood levels up, and I found it difficult to process iron pills, so we did this innovative treatment called iron infusion. Basically, it’s done almost chemotherapy-style where an IV is started and the iron goes directly into your bloodstream. For six or seven weeks, I had an iron infusion treatment every other day. My veins collapsed three weeks into it, and the needle marks in my arms made me look like I was a heroin addict. Thank goodness it was winter and I could wear longer sleeves. I also had a full body scan so that we could see all aspects of my chest cavity. Plus, I had a transesophageal echocardiogram, where a scope was put down my esophagus. The doctors found that my aorta had crystalized in places, so one of the risks they faced was not knowing where to exactly put the clamps because a crystal could break off into the bloodstream and travel to the brain and cause a stroke. But we really had the time to plan out every contingency. Because we’d caught it early enough, I could actually choose all of the aspects that would give me the best chance of survival and recovery. It sounds weird, but for all practical purposes it was elective open heart surgery. I was diagnosed on January 3; we went through the iron infusions, and the surgery was scheduled for March 17. I was told I’d be home to celebrate my birthday, and I was.

How long was the open heart surgery?

I think the procedure itself took 12 hours. My heart was out of my body for 22 minutes. The doctors told my family when I went on the heart-lung machine, and 25 minutes later they went back out and told them that my heart was pumping on its own. I was in the hospital for six days. Interestingly enough, I don’t remember anything that occurred. From day three, I remember just getting better. I was walking down the hallway; I had someone come and do my hair; I was demanding food; and my boyfriend at the time said that I started bossing him around, so he knew I was better. By day four, I had all my body function back. I could get up to go to the bathroom. By day five, there was no infection, and on day six I walked out.

What was it like convalescing?

At first, I had a recovery that was almost picture-perfect. I was lucky enough to have both my parents move to New York and stay with me. The first week, I was in bed. Week two, we had a visiting nurse come in to start at-home physical therapy, and that consisted of clearing my lungs and getting up and going to the bathroom by myself. By week three, I was moving in and out of the apartment and walking down the street. Week four was [to be] my challenge. I had to walk my hills at a very steep incline and get to the top without stopping. But I did it by week three. A lot of people don’t do outpatient physical therapy, and they don’t get the same kind of recovery. I signed on to go to the hospital three days a week for real physical therapy. Today, I am following a beautiful, wonderful regimen of cardiovascular exercise. I do an intense spin class in New York called SoulCycle a minimum of four times a week, or sometimes I’ll do as many as five or six. And I walk 30 minutes every day no matter what. I don’t think you ever could talk to somebody who is more grateful to be alive and able to be back.

What is the message you would like women in particular to take away from what happened to you?

That our health is our No. 1 priority. For many years, I thought my law degree was my greatest asset. It’s really not; my health is my greatest asset. If people would just do some basic modifications—such as remove the excess salt from their diet, stop smoking, get 30 minutes of exercise a day, exercise portion control and nutritional balance—if we’d just do those basic things, we’d reduce the incidence of heart disease in women.

1 Comment

1 Comment