In the early years of the AIDS epidemic, most Americans didn’t think that heterosexual men had to worry about the virus. It was primarily viewed as a gay disease, or one of drug users. All that changed on November 7, 1991. On that day, Earvin “Magic” Johnson stepped up to the podium at the Los Angeles Great Western Forum and told the world that he was living with HIV.

“It was a profound moment; I’ll never forget it,” says Nelson George, director of The Announcement, a recently released ESPN documentary that covers much of those early days.

“It really affected me and all of my friends, most of whom were single men in the early ’90s,” George continues. “[Magic’s disclosure gave] guys a reality check [that helped them understand] you’ve got to wear a condom; you’ve got to understand the concept of safe sex. It was a profound moment in the sexual life of America and the world because it took HIV away from being a disease that gay men get and made it something that heterosexuals had to deal with.”

What Johnson’s announcement showed was that anybody could contract the virus—even a legendary basketball icon, the epitome of health and vitality—making HIV everyone’s problem and everyone’s concern. But besides learning that the disease was not restricted to gay men, Magic got another lesson. “I learned quickly how differently I’d be looked at now that I had HIV,” he says in the film.

In 1987, four years before Johnson’s announcement, a congressional amendment put HIV on a list of “dangerous and contagious diseases,” where it joined AIDS, previously placed there by the U.S. Public Health Service under pressure from then-President Ronald Reagan. Interestingly, the government chose to designate HIV as “contagious” despite evidence the virus isn’t spread by casual contact, which is the usual public concept of what a contagious disease is.

Placing HIV/AIDS on this list meant people with the virus could not travel to the United States.

Today, almost 25 years later, the travel ban for people living with HIV is gone. President Barack Obama and Congress lifted the ban in 2010. That made it possible for the United States to host this year’s XIX International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2012). The conference comes to America for the first time in more than two decades and will be held July 22 to 27 in Washington, DC.

Immediately before the conference’s opening ceremonies on Sunday, Johnson will host an event called “Keep the Promise on HIV/AIDS.” It’s part of a declaration, march and rally endorsed by Johnson and orchestrated by the AIDS Healthcare Foundation (AHF). You see, Magic’s been very busy putting a full-court press on HIV/AIDS ever since he made that announcement almost 21 years ago.

Last December, Johnson revealed his plans to create a coalition to raise HIV/AIDS awareness, break down the stereotypes about the virus and engage rappers to speak out against homophobia and discrimination against gay people. According to an article in The Huffington Post Canada, Johnson says he reached out to the hip-hop community, a group he targeted because “they have power—power with their voice, power with that mic in their hand and power with the lyrics that they sing.”

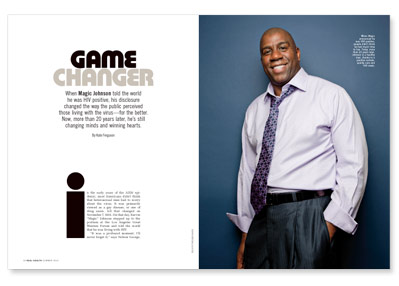

Johnson also knows a thing or two about the power of celebrity. When he announced his HIV status, Johnson was 32 years old and at the peak of his power and prowess as a b-ball star. When he walked away from the mic, though, he had a new direction on which to focus his considerable clout. He became an advocate committed to waging war against HIV/AIDS.

“But despite his HIV disclosure, he [and his wife, Cookie] were reluctant to do the documentary,” George says. “To go back and have people get the tapes and go through the minute details of every moment of [this experience] was something I think they didn’t want to do.”

George believes Johnson overcame his initial reluctance because doing the film gave him the chance to get people talking again about HIV. “The film worked as a kind of advocacy to get people who probably don’t think about HIV much anymore to put the virus back on their radar and restart conversations about it,” George says.

To kick-start that dialogue, when The Announcement premiered in Los Angeles, the Magic Johnson Foundation and AHF hosted a screening for high school kids, followed by a question-and-answer session with Johnson, Cookie and HIV experts and advocates.

“One of the most profound things about Magic doing the film is the way he reintroduced conversations about the virus to a community of young people who probably don’t really have a lot of consciousness about what HIV is, or who think, Well, [if you have the virus] you take a couple of pills and you’ll be all right, so what’s the big deal?” George says. “Johnson wanted to re-engage young people.”

Statistically speaking, Johnson’s right on target. Today, people ages 13 to 24 are at an increased risk of HIV/AIDS, with minority kids particularly vulnerable. “There’s this generation of 16-, 17- and 18-year-olds who need to be informed about HIV,” George says. “Using Magic as a tool for that was one of the film’s intentions.”

Certainly, Johnson’s rapport with young folks is real. One scene in the film shows Magic, shortly after his announcement, surrounded by a group of HIV-positive kids on the set of a TV special produced to educate young people about the virus. One of the children, a chubby-cheeked little African-American girl, bursts into tears when she explains she simply wants people to accept her for who she is instead of stigmatizing her because she has AIDS.

“She crystallized all of the discrimination that [HIV-positive] people faced at that time,” George says. “When I saw that footage, I said, ‘That’s got to be in the film!’”

That little girl, Hydeia Broadbent, grew up to be a passionate HIV/AIDS activist who works with Johnson’s foundation and speaks with L.A.-area youth about her experiences as a person living with AIDS.

But as a child, Broadbent didn’t know who Magic Johnson was. “When we went to the taping, I just knew I was there to talk about HIV/AIDS,” she recalls.

When she saw the new documentary, Broadbent learned something else she didn’t know back then. “As a young person I had no idea how much stigma Magic faced,” she says.

Broadbent’s admission echoes the ignorance many young people today have about the virus.

In the film, Johnson recalls learning about other people’s fears of HIV after David Stern, the NBA commissioner, agreed to let him play in the All-Star game. “Of course, I was excited about playing, but not everyone else was,” Johnson says.

Frankly, a lot of players were terrified. “Just like that little girl [Hydeia Broadbent], I was having my own problems being accepted,” Johnson says.

But in addition to the fear, a lot of people thought having the virus meant you couldn’t function anymore. Although he also lived with this fear, Johnson wanted to prove them wrong.

“Magic being able to come out and perform and show people he could still be in top form with the virus was a very important message at the time,” George says.

Even today, Johnson still dispenses key messages. He’s defied the odds that said he’d become a statistic after he contracted HIV.

Most recently, Johnson teamed with a Miami-based health insurer to create a comprehensive Medicaid plan for people with HIV/AIDS who live in underserved communities.

It’s a classic Magic moment: Fake ’em out then pass the ball for a huge crowd-pleasing slam dunk.

Important HIV/AIDS News

Magic is doing well on his HIV treatment regimen, but what about other black folks living with the virus?

Recent findings of the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) show that black women living with the virus are more likely to progress to AIDS and twice as likely to die of complications from the illness as their white counterparts—even when they are on a regimen of HIV meds called antiretroviral (ARV) therapy. But buried amid these alarming results is some really important HIV/AIDS news.

Why are black women’s HIV health outcomes so poor? Well, the answer is complex. WIHS findings also show the HIV-positive black women in the study were burdened with other known predictors of AIDS death, such as depression, high pre-treatment viral loads, low pre-treatment CD4 cell counts, hepatitis C coinfection and use of illicit drugs. In addition, previous research shows that African-American people are more likely to have a genetic mutation that can slow how quickly they metabolize HIV treatment drugs.

What’s more, researchers also found that another genetic mutation common among African Americans can negatively affect the concentration level of specific HIV drugs called protease inhibitors (PIs) in cells. (PIs block the cell’s use of protease enzymes, which are needed to create HIV. Thus, PIs prevent the cell from producing new viruses.)

Simply put, for anyone living with the virus, HIV treatment ain’t no crystal stair. Those who climb it face a multitude of challenges that constantly test their ability to stay adherent.

But for their HIV treatment to work, those living with the virus must take their meds as prescribed and regularly visit the doctor. This advice is supported by WIHS findings that show black women were 70 percent less likely to die of AIDS if they stuck with their treatment more than 95 percent of the time. That’s really the good news, says Kathryn Anastos, MD, a professor of medicine, epidemiology and population health at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, in the Bronx, New York, and the study’s principal investigator. Anastos stresses that to increase their chances of better health outcomes, black people living with the virus should focus on getting and staying in care.

In the meantime, scientists will do more research to find safer, more effective ARV therapies specially suited to African Americans.

Comments

Comments