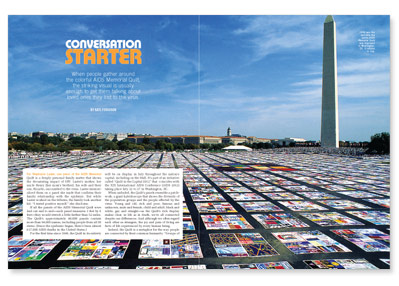

If all the panels of the AIDS Memorial Quilt were laid out end to end—each panel measures 3 feet by 6 feet—they would stretch a little farther than 52 miles. The Quilt’s approximately 48,000 panels contain more than 94,000 names, including people from all 50 states. (Since the epidemic began, there’s been almost 617,000 AIDS deaths in the United States.)

For the first time since 1996, the Quilt in its entirety will be on display in July throughout the nation’s capital, including on the Mall. It’s part of an initiative called “Quilt in the Capital 2012” that coincides with the XIX International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2012) taking place July 22 to 27 in Washington, DC.

When unfurled, the Quilt’s panels resemble a patchwork, a giant kaleidoscope that shows the diversity of the population groups and the people affected by the virus. Young and old, rich and poor, famous and unknown, male and female, child and adult, black and white, gay and straight—as the Quilt’s rich display makes clear, in life as in death, we’re all connected despite our differences. And although we often regard each other as strangers, the joy and pain of living are facts of life experienced by every human being.

Indeed, the Quilt is a metaphor for the way people are connected by their common humanity. “Groups of people who would never intersect with each other intersect on the Quilt,” says Jada Harris, the director of programs for The NAMES Project Foundation, the caretaker of this constantly evolving piece of art and historic memorial to millions. “I had two little old ladies in Montgomery, Alabama, who finished the panel for Jermaine Stewart, an R&B artist. Otherwise, they would never have met him.”

Although it’s hard to fathom two little old ladies—one on crutches, the other using a cane to support her steps—sewing Stewart, in lipstick and eyeliner, on his panel, there they were. In fact, it’s common for people to make panels for someone they didn’t know. “This is an example of the community coming together to memorialize someone who impacted the cultural landscape,” Harris says. Some students at Spelman College in Atlanta started Stewart’s panel, and the two women completed it.

“These two women weren’t concerned about Stewart’s sexuality, only about making sure his panel was very neat and clean and looked nice,” Harris says. “They created the panel with love. We don’t have a litmus test for people; the door is open to everyone; that’s what the Quilt does.”

In the 12 years she’s been working with the foundation, Harris has seen the creation of hundreds if not thousands of tribute panels to African Americans during workshops under the auspices of the foundation’s Call My Name Program. The workshops provide a kitchen table environment where people come and share intimate details of their lives because they need somebody to talk to. While they chat, their hands stay busy sewing or pasting on mementos that represent loved one’s lives. Here, they can talk freely, without worrying about stigma or shame.

“It took me 10 years to get the courage to put this panel together in remembrance of my brother, Rodney,” says Sonja Jackson, a 49-year-old from Clarkston, Georgia. “I miss him dearly, and through the process of working on the panel, I’ve experienced healing and spiritual growth.”

Jackson remembers her younger brother as a lover of life who had a passion for fashion, especially Izod and Polo clothing. That’s why she included a red Polo shirt on his panel and decorated it with some other things he loved, namely, a yellow sun and a silvery moon and stars.

Cleve Jones, a San Francisco gay rights activist, conceived of the Quilt 25 years ago when, like Jackson, he also dearly missed a loved one and wanted to pay tribute to his memory. Jones’s friend and mentor was Harvey Milk, the legendary openly gay San Francisco politician who was murdered in 1978 by former City Council member Dan White. (White also gunned down the city’s mayor, George Moscone, on the same day.) In 1985, when Jones helped organize an annual candlelight march honoring these men, he learned Frisco had lost more than 1,000 of its residents to AIDS. That gave him an idea. He asked people to write the names of their friends and loved ones who had died of the virus on placards. Jones and others then taped those placards to the walls of the San Francisco Federal Building. The collage created the look of a patchwork quilt.

Almost one year later, Jones produced the first AIDS Memorial Quilt panel in memory of Marvin Feldman, a friend he’d lost to AIDS. Then he launched The NAMES Project Foundation.

Almost one year later, Jones produced the first AIDS Memorial Quilt panel in memory of Marvin Feldman, a friend he’d lost to AIDS. Then he launched The NAMES Project Foundation.Flash forward to this summer and the Quilt in the Capital events: “Here we are 25 years later,” says Julie Rhoad, president and CEO of The Names Project Foundation. “And while we are still about advocacy and demonstration and all the things we were in the beginning, at the same time we are the preeminent cultural and visual response to this epidemic, and we have influenced many other responses.”

According to Rhoad, the Quilt motivates viewers to respond because the visual panels represent actual people, not statistics on a page. “[Early during the epidemic] the evidence was before me every day that my friends were dying,” Rhoad says. “We needed a way to lay out our dead in front of Washington to say, ‘These lives mattered.’”

Today, HIV/AIDS educators and advocates use the Quilt as dramatic evidence of the virus’s evolution in America. “You can see a point in time when mother-to-infant transmission drugs became more available because the panels for babies began to diminish,” Rhoad says.

The tapestry also provides a way to fight prejudice and raise awareness. Plus, the global AIDS community has used it as an effective tool in HIV education and prevention, Rhoad says.

Statistics show that the rates of African Americans living with the virus in some U.S. cities have surpassed those of some African countries. Black women, in particular, bear the biggest burden of death from the virus. “In Washington, DC, one in 36 African-American women are HIV positive,” Harris says. “That’s beyond a state of emergency.”

This alarming news is what the Quilt shouts to the world each time a panel joins the current tapestry. It’s also why Harris believes its show-and-tell function is tailor-made to use as a call to action.

Specifically, the Quilt can motivate government legislators who have the power to make a huge difference in the fight against HIV/AIDS.

“Call My Name is necessary to give people an opportunity to show what’s really happening in our community and the human toll the virus has taken,” Harris says. “It’s really about changing people’s consciousness so they can see what’s happening. Then, other things can fall into place—prevention efforts get ratcheted up, or people make better decisions in terms of their own personal behavior.”

But change for the better also requires that we eliminate the stigma and shame that are still so strongly associated with HIV/AIDS. These are the chains that stop many from disclosing their status and talking about the virus’s effect on their lives.

“Before Call My Name started, there were fewer than 300 African-American panels,” Harris says. “Today, I can confidently say we’re around the 400 or 500 mark.”

Despite this increase in numbers, African-American women don’t see themselves reflected often enough in Quilt panels—and that shortfall could cost lives because black women need to understand how dangerous HIV is to their health and well-being.

“There’s no question that the impact [of HIV] on African-American women is nothing short of tragic,” Harris says. “And yet we can’t call the names of them all because of that shroud of shame that’s associated with HIV. It’s a disease that comes with a lot of baggage.”

But some, such as entertainer Sheryl Lee Ralph, aren’t afraid to pick up the load and say the name of a loved one aloud. The actress and singer, who is a Call My Name program spokesperson and host, decided to make a panel for a sista, a popular disco singer who died of AIDS-related complications several years ago.

“I decided to make a panel for Sharon Redd,” Ralph says. “When people said women don’t get infected, I always knew that Sharon was infected. Some people called me stupid and told me I didn’t know what I was talking about.”

Ralph says she knows having Redd’s panel on the Quilt will help others step forward to break the silence about a disease that’s ravaging the African-American community.

“At some point, we’ve got to wake up and take care of ourselves,” Ralph says. “And if you won’t do it for yourselves, do it for your daughters because this disease is quickly becoming a young person’s disease. This is unacceptable because we’re no longer talking about color, we’re talking about young people, period.”

Jackson agrees with Ralph. Like the actress, she has gotten passionately involved in HIV advocacy and encourages others to call the names of their loved ones by adding them to the Quilt’s memorial panels.

“As long as we keep secrets, the disease is going to continue to run rampant in our community because we’re afraid to let people know,” Jackson says.

To this, there can only be one reply: Let’s speak up and call their names.

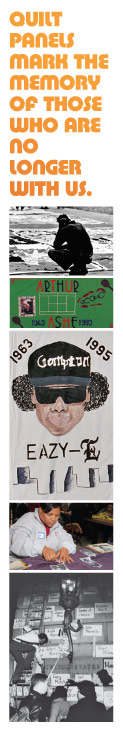

Gone But Not Forgotten

Tribute panels for loved ones lost to AIDS keep their memory alive.

Shelia Jones’s daughter, Samara, was 32 when she died of AIDS complications. To help others, the grieving mother became an AIDS advocate and spoke to young people in the Atlanta school system. She told then how the virus affected her and explained how important it was to become aware and active in the community in order to stem the epidemic’s tide.

To honor her daughter’s memory, Jones and other family members joined a branch of the Call My Name Workshop Program in their area and began work on a panel for the AIDS Memorial Quilt. “It’s been very helpful with the healing process because I’ve been dealing with her loss,” Jones says. “I wanted to convey her message about volunteerism and prevention because there’s still so much ignorance out there concerning this disease.”

Like hundreds of other people who lost loved ones to AIDS, Jones used the panel-making workshops as an outlet for her grief and to come to terms with her daughter’s death. “We let people work at their own pace, and we encourage them to complete their panels,” says Jada Harris, the director of workshop programs, which is overseen by the NAMES Project Foundation, the caretaker of the Quilt.

This year, Merck, the pharmaceutical company, is working with the NAMES Project to sponsor the Call My Name national tour. The mission? To bring attention to rising HIV transmission rates in African-American communities.

The tour kicked off in Atlanta in February and ends at a panel dedication ceremony at the XIX International AIDS Conference this July in Washington, DC.

Currently, the Quilt is on tour as it makes its way to DC, where it will be displayed in its entirety—nearly 48,000 panels in all—giving many people a chance to view the memorial and keep the memories alive. As Harris says: “The Quilt tells the stories of hundreds of thousands of people’s lives.”

If you have a story to tell about loved ones lost to AIDS, contact the NAMES Project Foundation at 404-688-5500 or visit aidsquilt.org.

1 Comment

1 Comment